Tl;Dr: It’s okay if your brain and body want sex when you are stressed. It’s okay if they want it less. Both are normal—even during a pandemic and an uprising. There’s science to prove it. Research also shows that big feelings (like fear of getting sick, or anger at injustice) can be processed and released before they do lasting harm to you or your life. I share excerpts from Emily Nagoski’s book Come As You Are and two others to show how we might be able to use kink to do the same thing.

This article is around 11200 words. If you’re not interested in the neuroscience of sexual brakes and accelerators or why we don’t have sex drives, you can skip to “How to stop stopping: taking your foot (and everything else) off the brake” to learn about using emotions to release stress. If you’re very low on energy and just want help, jump to “Completing the cycle while (ahem) laying in bed” for my recipe on how to use size kink to achieve that catharsis.

(Content tags: This article contains mentions of the pandemic, police brutality, racism, violence, murder, assault, AIDS, PTSD, depression, anxiety, and trauma responses. It also covers topics ranging from BDSM and impact play, to polyamory, to microphilia/macrophilia, and covers size dysmorphia and kink-related fantasies. I welcome help in tagging—please let me know when I have missed anything important.)

Sections in this article

- Sex in a tinderbox

- What a sex-research nerd can tell us about getting hot under pressure

- The audience for this book

- Sexual Accelerators & Sexual Brakes (half the point of this blog post)

- Are there differences for different genders?

- How to stop stopping: taking your foot (and everything else) off the brake

- You didn’t answer the question. How do I stop putting the brakes on?

- Completing the cycle while (ahem) laying in bed

- Everything we’re describing happens all the time in kink

- What this looks like for me: stress cycle sprints with a sizeshifter

- Are you ever small instead? What if you still feel upset at the end?

- What’s next? Size-themed guided meditations? Somatic revolution?

- The erotic as power

- The community part of “kink community”

Introduction

I didn’t expect that it would take a pandemic and a racial justice uprising for me to finally sit down and write a review about a phenomenal book on sex research for my kink blog. Here’s the reason I hope you’ll read this. People are having huge emotional responses that they don’t have the space or tools to fully process; they are also judging others/feeling ashamed for not wanting sex right now, while others are having the same response to those who do want sex right now. Research shows sex desire can decrease for some and increase for others during times of great stress, and that both are normal and healthy. Sex-positive spaces like #SizeTwitter should make space for both responses, and might already be able to provide tools to help process big emotions.

Frankly, I can think of so many articles I’d rather you spent your time reading at this moment. An argument for sex-positive research-informed kink community spaces should be lower on the priority list than the fight for justice. I also believe that sex-positive rest for resistance is one part of our work in dismantling systems of oppression.

I began writing this article in early June, and wasn’t able to continue it until July. I’m not able to protest in person for multiple reasons, and have focused my energy on my nonprofit work and also with helping fellow white allies self-educate. This is one angle I haven’t seen addressed yet in any of my circles, so it seems worth speaking up. Please share similar resources in the comments if you’re aware of them.

It’s worth noting that I am not advocating that we use sex to numb our pain or avoid action. To quote the powerhouse activist and writer adrienne maree brown in the brilliant Pleasure Activism, which draws on a legacy of Black feminist tradition:

“We are in a time of fertile ground for learning how we align our pleasures with our values, decolonizing our bodies and longings, and getting into a practice of saying an orgasmic yes together, deriving our collective power from our felt sense of pleasure. I think a result of sourcing power in our longing and pleasure is abundant justice—that we can stop competing with each other, demanding scarce justice from our oppressors. That we can instead generate power from the overlapping space of desire and aliveness, tapping into an abundance that has enough attention, liberation, and justice for all of us to have plenty.”

Toni Cade Bambara wrote that we should make the revolution irresistible. Audre Lorde argued that the erotic is a source of power.

This article is an invitation to my small kink community to accept that our responses to sex can change, and that certain ways of turning to sex or fantasy in a time of great pain can be healthy and empowering, and support us in the marathon we face as agents of change.

Sex in a tinderbox

The world is a terrifying place right now, and our nervous systems are responding accordingly. Police brutality, violence, and murders are taking center stage in a historic uprising, a vitally important fight for justice centuries in the making. Humanity is months deep into the mortal fear, grief, and painful isolation of a pandemic. We’re in a tinderbox at a tipping point, with both Gen Z and Millennials driving the demands for change, double the number of generations than Straus and Howe predicted. To anyone who has prior experience with PTSD, the world is brimming full of people having trauma response after trauma response.

In times of great pain and grief, our dominant cultural narrative expects people to stop being interested in sex and will judge people for feeling sexual. The widest part of the bell-curve does respond that way, most of the time. But there are a significant percentage of people who respond instead by wanting sex more intensely.

Both are normal. And in the midst of trauma responses, it’s normal to oscillate between these extremes.

What a sex-research nerd can tell us about getting hot under pressure

Since I read it seven months ago, I’ve been wanting to use my small platform here to review Come As You Are: The Surprising New Science that Will Transform Your Sex Life for at least a dozen reasons. I’ve been raving about the insights and the changes it has brought to my life, I’ve convinced at least five friends (that I know of) to read it. I adore Nagoski’s delight and enthusiasm in her author-read audiobook. If I’m being honest, I find her voice both reassuring and arousing. I admire her passion for her work; if my friends and I are any indication, it’s a passion that’s catching.

I’ve taken courses on human sexuality, was raised in a sex-positive household, and was still flabbergasted by the things Nagoski taught me that I never, ever knew. Some highlights:

- Homologues in anatomy — “All the same parts, organized in different ways”

- Arousal non-concordance — basically, lubrication does not equal causation; “genital response doesn’t necessarily match a person’s experience of arousal,” to the point where 50% of cisgender male research subjects had an overlap between genital response and subjective arousal… and only 10% for cisgender female subjects. A physical response is just a response, and cannot tell you if the person enjoyed it.

- Sexually-relevant stimuli — how kinks develop (where was this when I was a teenager frantically asking Jeeves how to get rid of a fetish?)

- Responsive sexual desire — the standard narrative of sexual desire is that it just appears spontaneously, but some people find that they want sex only after erotic things are already happening. Both are normal and healthy.

- Sex isn’t a drive, it’s incentive — the idea that sex is a drive like hunger or thirst grants it a privilege it doesn’t deserve and means we invent justifications for people who use any strategy for relieving that urge. Sex is actually an “incentive motivation system,” like curiosity.

The audience for this book

Is this book for everyone? Does it cover research on everyone? Well, yes, and no. One frustrating dimension of Come As You Are that the author talks about is the relative lack of research on sexual experiences of trans and gender non-conforming people, and how most of this relates to asexuality (she does touch on ace experiences).

Many of the myths debunked in this book center around research on cis women’s sexuality, with plenty to learn about cis men’s sexuality along the way. I am frustrated by the fact that there’s a wealth of knowledge here that applies to people of all genders, but because of the heavily gendered research and marketing of this book for a cis female audience, others might miss out on what it can offer. I sincerely hope that this work, and her follow-up book Burnout that she wrote with her sister, will pave the way for other sex educators and trauma researchers to take this work further, to demand better research, to consider voices, perspectives, and injustices from communities of color, people with disabilities, and other intersecting identities.

So while there are insights available for anyone and everyone in this book, and while the author uses inclusive queer-focused data and anecdotes whenever possible, it also highlights the need for more research and funding beyond the binary to capture more of the human experience.

Sexual Accelerators & Sexual Brakes (half the point of this blog post)

Here is half the reason I wrote this blog post for you. Forget the outdated notion of a “sex drive,” which Nagoski debunks easily. Try this on for size instead.

Quoted from the summary at the end of Chapter 2:

- “Your brain has a sexual “accelerator” that responds to “sexually relevant” stimulation—anything you see, hear, smell, touch, taste, or imagine that your brain has learned to associate with sexual arousal.

- Your brain also has sexual “brakes” that respond to “potential threats”—anything you see, hear, smell, touch, taste, or imagine that your brain interprets as a good reason not to be turned on right now. These can be anything from STDs and unwanted pregnancy to relationship issues or social reputation.

- There’s virtually no “innate” sexually relevant stimulus or threat; our accelerators and brakes learn when to respond through experience. And that learning process is different for males and females.

- People vary in how sensitive their brakes and accelerator are. Take the quiz on page 71 to find out how sensitive yours are—and remember that most people score in the medium range, and all scores are normal.”

This is why you can do all the things that usually turn you on—your favorite fantasy, your buzziest toy, the loving partner who you find very attractive, your trusty shrink ray or growth potion—and sometimes, your body and brain just won’t respond. No erection, no lubrication, no interest. No matter how hard you press on the accelerator, you’re not going anywhere if you don’t take your foot off the brake.

This was a revelation for me. Context, emotional state, fears, anger, unresolved trauma responses, all of them can put more and more pressure on the brake. Your brakes may go on because of internal fears (Why am I taking so long to get turned on? Shrinking roleplay usually gets me so horny!) or external fears (What if they really secretly want me to be the Giantess right now, instead of the tiny?).

There is nothing wrong with not wanting sex in this state. There is nothing wrong with wanting it, too, and it’s okay if you want it more or less than your partners, friends, or people in shows or film.

Because, for me at least, that’s the second part of this revelation. Some people’s brakes are super sensitive. Some people’s accelerators are, instead. And these natural impulses influence our behavior and habits (and probably the amount of time we spend scrolling through kink Twitter).

What happens when you have a sensitive accelerator (easily turned on) and hardly any brakes (not easily turned off)? Well, that’s when, three months into a pandemic, you might make yourself a third Size Roleplay account at 2am on a Thursday because you’re so stressed and so horny you can’t sleep.

“The sensitive accelerator plus not-so-sensitive brakes combination describes between 2 and 6 percent of women, and it’s associated with sexual risk taking and compulsivity. Because the brain mechanism responsible for noticing sexually relevant stimuli is very sensitive, you’re highly motivated to pursue sex, and because the brain mechanism responsible for stopping you from doing things you know you shouldn’t do is only minimally functional, you may sometimes feel out of control of your sexuality, especially when you’re stressed. You’re likely to have more partners, use less protection, and feel less in control. You might also be more likely to want sex when you are stressed (“redliners”), whereas other women are likely to find that their interest in sex plummets when they’re stressed (“flatliners”).”

When I first read this book, I wondered if I fell into the “flatliners” category, sensitive brakes, because my desire for sex has been known to plummet unexpectedly. On reflection, I think it’s more likely that I’m more the middle of the bell curve, but kept piling more and more stressors on a fairly standard brake.

In the Before Times, Nagoski’s chapters on how to take your foot off the break helped me process stress in tangible, profound ways. These days, they’ve become even more vital. More on that in a moment.

Nagoski offers a quiz in her book to help you get a sense of your inclinations, and provides insight for each of the six combinations. For example, if you have sensitive brakes, “you’re pretty sensitive to all the reasons not to be sexually aroused. You need a setting of trust and relaxation in order to be aroused, and it’s best if you don’t feel rushed or pressured in any way.”

Or if you have an accelerator that’s not very sensitive, you might need to “make a more deliberate effort to tune your attention in that direction.” Unusual situations aren’t likely to turn you on as easily as familiar situations, and using a vibrator may be a way to increase stimulation into a range that suits you. This is also “associated with asexuality, so… you might resonate with some components of the asexual identity.” And this is normal and healthy. As she writes in a footnote, “Again, there’s nothing broken or wrong; asexual people’s sexual response mechanisms are made of all the same stuff as sexual people’s, they’re just organized in a different way.”

I can think of people within our small kink community who fit all of these descriptions. I can also think of times when I compared myself to them without even thinking about it, wondering if there was something “wrong” with me.

But really, there’s nothing wrong with any of us. We all belong.

Are there differences for different genders?

According to the research on cisgender people, on average men have a more sensitive accelerator, and women have more sensitive brakes. This may be largely due to the fact that a penis going erect makes it easy for a person to figure out what is sexually relevant to their body. However, people with vaginas don’t have the same sort of obvious physical and visual cue. As a result, research on cis women shows that they usually learn to link “sexually relevant” to social context instead.

Fun fact: height varies between men and women, but it varies more within each group than it does between the groups. Likewise, there is a huge range of accelerator/brake sensitivities within each gender.

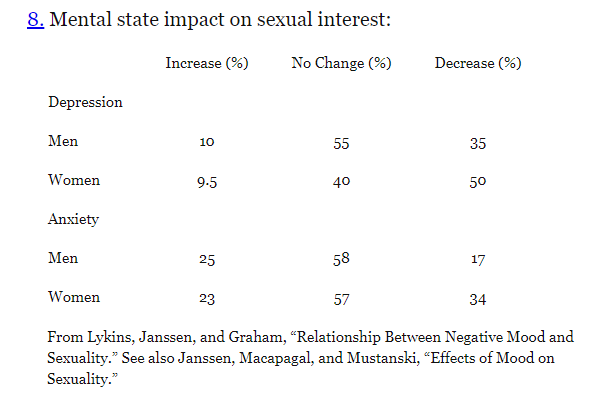

For the purposes of this blog post, it’s more relevant to talk about the influence of mood and anxiety on sexual interest for different genders. Did you know half of cis women have decreased sexual interest when depressed, but only 35% of cis men have the same response?

Chart from the footnotes, tracking mental state on sexual interest:

Yet more reasons to go easy on ourselves and other people in our kink community right now. The U.S. Census Bureau recently reported that a third of Americans show signs of clinical depression and anxiety right now, and the numbers are on the rise.

How to stop stopping: taking your foot (and everything else) off the brake

(content tag: this section uses a lion attack to discuss trauma responses)

If our bodies respond to stress by putting the brakes on arousal and pleasure, how do we take our foot off the brake? Why isn’t it enough to hit the gas pedal to try and overpower the brake?

There’s no easy way for me to summarize or do justice to Nagoski’s phenomenal chapters on this concept. In fact, she couldn’t do it justice, herself. These chapters played such a pivotal role in helping her readers heal that Emily and her twin sister Amelia Nagoski took them and turned them into Burnout, another profound and fantastic book that I’m even faster to recommend to people than Come As You Are.

(For a phenomenal critique of the limitations of the white feminist, cishet, ablebodied, and neurotypical perspectives of this book, which also apply to Come As You Are, I recommend the podcast series Big Strong Yes, specifically the episode “The Gold is Love“.)

Burnout includes excellent tips on how to dismantle the patriarchy, love your body, and even more wonderful ways to complete the stress cycle.

“Complete the what cycle?” I hear you ask. Right. I’m getting ahead of myself. In Chapter Four of Come As You Are, Nagoski breaks down the science of the physiological, neurological, and emotional responses that get stuck on our brakes.

Stress is the body/brain process that helps us deal with threats, and developed back when our threats had “claws and teeth and could run thirty miles an hour.” On the other side of that, love is the body/brain process that helps us connect with our people, our families and community, in a way that reassures our body/brain that we are safe from the aforementioned claws and teeth.

“The key to managing stress (so that it doesn’t mess with your sex life) is not simply ‘relaxing’ or ‘calming down.’ It’s allowing the stress response cycle to complete. Allow it to discharge fully. Let your body move all the way from ‘I am at risk’ to I am safe.’”

I’m going to repeat that, because it really is that important. The way out of stress is not by ignoring it or distracting from it, but to move through it. The way to move through stress is to allow the stress response cycle to complete.

She uses a lion scenario to talk about threat responses. When you encounter the lion, your brain has at least three options to choose from—fight, flight, and freeze—and opts for the one with the highest survival rate: you run. You either do or don’t make it home, but if you do, your village helps you defeat the lion, tend your wounds, and celebrate how relieved you are to be alive and among people who love you.

That, in a nutshell, is the stress response cycle.

Fight and flight are accelerator stress from the sympathetic nervous system. But the one most people aren’t familiar with, freeze, involves the parasympathetic nervous system. The brakes. Everything shuts down, because if the lion has her teeth in you, your body’s absolute last and best defense is to convince the predator you are already dead. What comes next is a revelation.

“If an animal survives such an intense threat to its life, then it does an extraordinary thing: It shakes. It trembles, paws vibrating in the air. It heaves a great big sigh. And then it gets up, shakes itself off, and trots away. What’s happening here is that freeze has interrupted the GO! stress response of fight or flight, leaving all that adrenaline-mediated stress to go stale inside the animal’s body. When the animal shakes and shudders and sighs, its body is releasing the brake, completing the activation process triggered by fight/flight, and purging the residue. Completing the cycle. It’s called ‘self-paced termination.’”

Turns out, people do this when coming out of anesthesia. We do it when coming out of violent experiences, like an assault or a riot or a disaster. You do it in small ways when you leave a stressful day at work and your body is craving an hour at the gym so you can punch something or run five miles on a treadmill. Ever screamed into a pillow? Or panic-scrubbed an entire kitchen while on a work deadline? Your nervous system is naturally trying to complete the cycle.

What happens when we don’t complete the cycle? Freeze after freeze. Depression and anxiety. Sudden panic attacks as your body’s flight/fight impulses burst through the numbness of endless freeze. All of these are trauma cycles looping endlessly because we shut them down to stay “civilized.” Sometimes we do need to shut them down in the moment to stay safe, parent our children, keep our jobs, and face down a line of cops in riot gear. But if you never make time later that day or week to feel and release those emotions, guess what? You’re stuck in the cycle.

A single unprocessed traumatic event can follow you your entire life, and what happens when you start collecting them?

The good news is that you can complete old cycles, even ones buried beyond the reach of your memory. The bad news: suppressing and avoiding your emotional truth means you surrender your personal power, year after burned out year.

Quoting Nagoski:

“To sum up:

“Worry, anxiety, fear, and terror are stress—’There’s a lion! Run!’

“Irritation, annoyance, frustration, anger, and rage are stress—’There’s a lion! Kill it!’

“Emotional numbness, shutdown, depression, and despair are stress—’There’s a lion! Play dead!’

“And none of these indicates that now is a good time to get laid. Stress is about survival. And while sex serves a lot of purposes, personal survival is not one of them (except when it is—see the attachment section). So for most people, stress slams on the brakes, bottoming out sexual interest—except for the 10 to 20 percent or so of people… for whom stress activates the accelerator. (All the same parts, organized in different ways.) But even for these folks, stress blocks sexual pleasure (enjoying) even as it increases sexual interest (eagerness). Stressed sex feels different from joyful sex—you know, because: context.”

Her argument for having more joyful, pleasurable sex? Manage your stress. Obviously, this is easier said than done.

(Update to the article) There is a fourth more recently identified response, fawn. According to The Mighty, it’s “a term coined by Pete Walker, a C-PTSD survivor and licensed marriage and family therapist who specializes in helping adults who were traumatized in childhood.” Basically, it relates to that “made it home safe” part of the cycle. When home isn’t safe, it’s how more recent mammalian parts of our nervous system work to reconnect with our social ties that keep us fed, sheltered, cared for. (CW for abuse mention in the video) This video by Irene Lyon, MSC and nervous system expert, sheds some light on it: What is the fawn response? Nagoski addresses it briefly in the section on attachment, but I’m not sure why she doesn’t go deeper with it given the context.

You didn’t answer the question. How do I stop putting the brakes on?

Managing your stress basically amounts to getting yourself into a context where you can safely feel and express all your big feelings, take your foot off the accelerator and the brake, and allow yourself to coast to a stop.

“Physical activity is the single most efficient strategy for completing the stress response cycle and recalibrating your central nervous system into a calm state. When people say, ‘exercise is good for stress,’ that is for realsie real.’”

Her advice? Run, walk, dance, play sports, have “a good cry or primal scream,” or even just jumping up and down. She writes about other things that will help the body complete the cycle, like sleep, affection, creating art or music, and any form of meditation like mindfulness, yoga, tai chi, body scans.

I’ll be honest, I read that section of Come As You Are so many times that it’s the most highlighted part of my e-book. I read it while depressed and before crying myself to sleep. I read it while sitting in my car in January, begging my body to brave the cold so I could get inside, jump in a swimming pool, and scream my body through the water, propelling myself away from every real-life stress I could conjure. I read it again after exercise, listening to it as an audiobook while I painted my nails or dyed my hair, trying to reconnect with my “rituals of self-kindness” that Nagoski compares to primates grooming each other to bond. It helped. It changed my life.

Then the pandemic hit. Quarantine meant even my love-hate relationship with my gym had to go on hold. Exercise options shrank to a list that was distressingly small—even for me. It wasn’t until I read the book Nagoski wrote with her twin sister, Burnout, that I found an option to work even on my most intensely stressful and trauma-immersed days. Keep reading and I’ll treat you to a description of how I do this while sizeshifting.

Completing the cycle while (ahem) laying in bed

What do you do when you can’t exercise—or even if you can exercise sometimes, but not every time you have big emotions? I don’t know if your year has been anything like mine, but I’ve found myself coming down off hours of exercise and processing big emotions, only to get a message from a friend in deep pain or scroll past something that hits my trauma buttons in just the right way to send me reeling again. I can’t spend every waking minute outside exercising, especially in July in Texas.

So, for anyone whose ability to move has been impacted by COVID, quarantine, chronic illness, disability, injury, mental illness, or lack of time to yourself… there is hope.

This excerpt from Burnout centers on an anecdote with a fictional woman named Sophie who is a composite of multiple women interviewed in the research. She’s represented as a Black engineer and self-professed geek who dislikes exercise for a variety of reasons.

“Okay, so just lie in bed—”

“My favorite sport,” Sophie said.

“Then just progressively tense and release every muscle in your body, starting with your feet and ending with your face. Tense them hard, hard, hard, for a ssslllooowww count of ten. Make sure you spend extra time tensing the places where you carry your stress.”

“Shoulders,” Sophie said instantly.

“Super! And while you do that, you visualize, really clearly and viscerally, what it feels like to beat the living daylights out of whatever stressor you’ve encountered.”

“Okay,” Sophie said with some enthusiasm.

“Imagine it really clearly, though—that matters a lot. You should notice your body responding, like your heart beating faster and your fists clenching, until you reach a satisfying sense of—”

“Victory,” Sophie said. “I got this.”

She did. And strange things started to happen. Sometimes, when she was doing the muscle-tension activity, she felt inexplicable waves of frustration and anger. Occasionally, she’d cry. Sometimes her body would seem to take over and shake and shudder in strange ways, as if she were possessed.

She emailed Emily about it.

“Totally normal,” Emily assured her. “That’s your baggage unpacking itself. All those incomplete stress response cycles that have built up inside you are finally releasing. Trust your body.”

It’s worth noting that Burnout also gives guidance for the part of the cycle that brings you home from the lion—not just outrunning it, but convincing your body that you are safe among loved ones. (It doesn’t have to be people—pets definitely count!) Kisses over six seconds and hugs over 20 seconds are both likely to help your all-important Vagus nerve calm down. My polycule began doing this when my metamour and I read Burnout and we can confirm that it has helped a surprising amount. I felt silly counting the duration of a hug, but less silly when I began to see a genuine shift in my body after around 12-14 seconds each time.

(Update from summer of 2021: I can say with confidence that 20-second hugs are the best, and have been profoundly helpful in maintaining my mental health. It stopped feeling strange by autumn of 2020. I do recommend asking first: “Would you be up for a hug? Long or short?”)

I know that kisses and hugs aren’t possible for everyone right now for many reasons. As a polyamorous person who will never be able to spend every night (or sometimes, any nights) with my partners, I know firsthand that mimicking an embrace with a pillow or teddy bear when you’re lonely can feel painful and hollow. But if it’s the best you’ve got then it’s the best you’ve got, and it’s still worth a try.

There’s some evidence to suggest that a significant percentage of our minds don’t know that the people we encounter in movies, shows, and books aren’t real. (One of the reasons running through all the seasons of of your favorite show in quarantine can feel so good—your brain may feel some kinship and safety with the recurring characters.) Nagoski also points out that art can be a good way to complete the cycle—especially with stories that have a big emotional component to give you catharsis.

The hardest thing about completing the stress cycle is that it’s not enough to just intellectually decide to be done with an emotion, or to tell yourself everything is fine now.

You have to physically do something. It’s a physiological shift in your body. The only way out of an emotion is through it. And the only way through it is to use your body, in whatever way you can.

Which brings me to our next section. What does this have to do with kink?

Everything we’re describing happens all the time in kink

So, as a person who’s been exploring kink since the early 2000’s and who connected with the community in 2015, I have to admit that I see a ton of parallels between the releases of the stress cycle and the kinds of activities that people pursue in kink spaces.

There are many ways to define kink, with many variations and subcultures. “BDSM” is a common umbrella term that involves consensual exploration of power exchanges, sometimes causing and receiving pain, as well as role playing scenarios that can become intensely emotional. It’s not unusual for people to cry in kink spaces. They push themselves physically, mentally, and emotionally, and find ways to face their traumas on their own terms.

Consider this excerpt from The Bottoming Book, by Dossie Eastman and Janet Hardy, which is well worth the read if you’re interested in kink, as is the companion edition, The Topping Book.

(Content tags for grief, death from AIDS, and consensual physical violence in the form of flogging.)

We value these scenes for the emotional release they bring, and our partners usually value sharing in the process. Next time it might be our partner’s turn—catharsis works from the top as well as from the bottom. It helps to let prospective partners know that if you burst into tears, or become enraged, it’s what you want, and that whatever they are doing, it’s obviously working.

For example, Dossie recalls an intensely emotional flogging scene at a party that was fueled by the fact that a close friend of both Dossie and her top had died that week of AIDS. She had been an important member of the community, indeed the founder of the Society of Janus, and virtually everybody at the party knew her and was moved by her death.

As David flogged me, I felt myself go into intense sadness, almost crying, and then felt overtaken by equally intense rage, that seemed to have nowhere to go until I reared up, turned to my top in the presence of a lot of people, and screamed: “You stupid fuck can’t you hit any harder than that?” This would be a seriously rude maneuver in most scenes, but we were in the flow and David understood perfectly. Grinning wolfishly, he swung his arm back and gave it all he had. I let my rage pour out, and fell again into sadness, then reared up again screaming in rage, with David flying right along with me. Round and around we went until the rage was satisfied and I fell down crying—he fell right on top of me, and we both cried until we were satisfied. And both agreed there was something magically right about this scene, that in struggling against each other we had done just what we needed to do for funeral games.

Most scenes aren’t that intense. Most emotional cycles aren’t that intense. But they can be. Whether they are large or small, sigh-worthy or sob-worthy, odds are good that getting them out will help reduce the physical, mental, and emotional load you are carrying—and which may have settled squarely in the center of your sexual brake and accelerator system.

One other vital thing: What usually happens after kink scenes? Aftercare. Cuddles and hugs that last far longer than 20 seconds. Loving kisses and comfort. Verbal and physical reassurances that you are safe. This social bonding time sounds exactly like the happy ending of the lion-chasing scenario, doesn’t it?

One of the fascinating things about practicing kink in an online space like #SizeTwitter, as opposed to face-to-face, is that most people in the community develop keen visualization abilities. Remember how much Nagoski stressed the importance of visualizing during the muscle tension exercise? Visualization is a skill like any other, and people who discover that their bodies respond to fantasies that aren’t physically possible in the real world—such as sex with a Giant or tiny person—have lots of motivation to build that skill.

I consider this really good news. So many writers, artists, readers, and fans in our community have phenomenal imaginations. Some, like me, have additional sensory input from size dysmorphia that encourages my brain to turn to fantasy and visualization almost by instinct, just to mentally coexist with the weird things I feel. Regardless of the reason, it seems that the more visceral your visualization, the more effective you will be at processing big emotions and trauma during these exercises.

Looking at the many kink “subgenres” that are common in our community, it looks to me like we’re already doing some of this work. Some of my favorite “Giantess rampage” fantasies and fiction were borne from a need to invoke and process rage. Many of my shrinking fantasies help me process fear, shame, and humiliation. Hell, the nonconsensual shrinking story I wrote for Size Riot’s 2019 Cruel January contest was so dark and powerful for me that I still haven’t been able to repost it here to my blog. But writing it for myself and my community in the contest was a deep release for me in a healthy context.

In a section of The Bottoming Book called “Getting Bigger, Getting Smaller,” Eastman and Hardy write, “Some bottoms see themselves as warriors, conquering an ordeal, an initiation, triumphing over obstacles presented by their top… Others, or maybe the same people at different times, want to get small. They want to become invisible, helpless, overwhelmed, they want to dissolve. They love to enter into the struggle and lose, to be conquered, to give it up to a powerful and inexorable top.”

See any hints of fight, flight, freeze, or fawn in that description? Whichever way you invoke your emotion, whether it’s to shrink down into the smallest speck or grow to rival the Earth itself, you may already be using kink to transmute your pain into pleasure. The release of a climax in this context is a double release, as you let all the feelings go.

Hopefully, you have a safe structure to hold you as you do this—boundaries, communication, safewords, a plan for aftercare, and play partners ready to hold space for your pain and your pleasure. “BDSM allows us to experience things safely that would not be okay in the real world,” write Hardy and Eastman. “We can feel the adrenaline rush and the head-spinning loss of control that highlight [nonconsensual] fantasies—while placing our emotional and physical safety in the hands of someone we trust… We can consciously transform that which is scariest and least acceptable into acts of trust, intimacy, learning, and healing.”

I’m still surprised that Come As You Are doesn’t address the potential for kink to help people complete their stress cycles, but it will be the first thing I ask Emily Nagoski if I ever get the chance.

What this looks like for me: stress cycle sprints with a sizeshifter

(Content tag: descriptions of fantasies where evacuated cities are destroyed)

One of the reasons I’ve had the motivation to write this in early July is that I’ve been knee-deep in processing a personal trauma for the last two weeks. I’ll spare you the details of the stressor—it boils down to a fight with family members with potential long-reaching consequences, a situation which my therapist says has “challenged my nervous system’s sense of safety.” Here’s what it’s looked like for me to process the stress itself in the context of my kink and size dysmorphia.

The first week I was able to manage the stress by letting myself cry and grieve when I needed to, and by going outside for exercise. In quarantine, the open sky has become a kind of sanctuary for me to stretch myself and feel huge without the accompanying sense of being trapped.

For context, the early months of quarantine were confusing for my size dysmorphia, giving me Giant claustrophobic feelings as I spent 20/24 hours a day on average working and sleeping in the same room with low ceilings and one window—offset by small panicky feelings and endless, energetically empty Zoom calls with people holding their devices at low angles.

By contrast, going outside where I can breathe and feel big is a tremendous relief. I count my laps, let my body get into a rhythm, and after I have warmed up I spend some of each session actively thinking about the stressor while pushing myself as hard as possible for short 10-15 second bursts.

I learned about Tabata-style workouts at my gym last year where a trainer had us push ourselves to give 100% effort for 30 seconds, switch to low-stress jogging, then 100% for 20 seconds, another low-stress jog break, and then finally 100% for 10 seconds. I discovered that I could fuel these bursts by imagining myself taking a baseball bat to my work computer or physically shredding the paperwork that gave me stress nightmares. I learned I could expand that by visualizing all kinds of stressors, and that has been the basis for my quarantine exercise as well.

So I use these stress cycle sprints to bring myself into high intensity emotional purges. When I’m pushing myself physically, they come to the surface much more easily. Loud, angry music helps. Outdoors during quarantine, I usually find myself sizeshifting to enormous proportions as this happens.

Near my favorite place to exercise, 100-ft tall power lines stretch over the neighborhood. It’s become a habit to glance at those and gauge my internal body sense for how large I become on any given day. Some days I push myself hard and feel like I am 20, 50 feet tall. I visualize myself breaking apart buildings with my bare hands, uprooting trees, smashing craters into asphalt with my feet.

If I can glance around and confirm that nobody is within earshot, I will let myself shout and yell and groan as I do this. (One surprising benefit of exercise with a mask on!) On my most frustrating days, I grow as tall as the power lines or taller, and imagine taking the metal supports and swinging them like absurdly huge baseball bats and demolishing whole swaths of neighborhood.

Those of you who have followed me for long know that physical violence is among my hard limits due to past PTSD, so these visualizations never involve people. Some days I have to include “this place has been evacuated” caveat to my imagination or my heart will not be able to access my rage. However, I understand how and why many people in this kink community and others find those kinds of fantasies to be cathartic.

My feeling on that remains: as long as every real person involved in your fantasies is a consenting adult, you do you. (Remember, people who encounter art and writing online cannot give fully-informed consent without content tags to let them opt in or out.)

Some days these stress cycle sprints push me into tears. In the last two weeks, they’ve pushed me into body-wracking sobs on multiple occasions. One woman saw me sobbing and hyperventilating into my mask in the shade of a tree and got worried until I waved her off. I know for me, it helps to find spaces and times of day where I can exercise without many people around, so I feel more free to express and release what comes up.

It’s scary, but it’s also deeply cathartic. Afterward I often feel like my size is more under my control, and I can face the rest of the day with far more calm and emotional energy than I could before. Depending on stress levels, the effect lasts for days.

Sometimes when I exercise for longer periods of time, I like to listen to podcasts or audiobooks, and I’ve learned that I cannot bring myself to a stress cycle sprint while low-key disassociating this way. I have to set aside time in my workout to turn off the distraction, crank up music that invokes the right emotional response, and deliberately sit with the discomfort of my stress. Feeling the emotion is the only way through it.

Within the last week, I was hit with waves of debilitating nausea. My therapist hypothesized it was stale adrenaline from constantly cycling through my fears and not processing or releasing my trauma. I was making time to exercise, but it wasn’t enough. I had to work. How do I move through a stress cycle while trapped in this room attending four-hour zoom meetings? And even when I had time to exercise, how could I face 100-degree Texas summers while so nauseated I couldn’t keep food down?

Enter the muscle exercises from Nagoski’s Burnout. Here’s what that looks like for me.

I close my laptop and turn out the lights to signal “this is not work time,” then lay down in bed with headphones. I put on a song that I have come to associate with my sprints (for me, “Invisible Chains“ by Lauren Jauregui), then close my eyes and let myself grow.

I’ve been trapped in a cage

Sorrow said I should stay

But I found beauty in this pain

Gave me strength to break these

Invisible chains

As the music builds, I invoke what is stressing me, pull it into my mind and put a spotlight on it. I tense groups of muscles as hard as possible—my feet and calves and thighs—and hold as tightly as I dare. After about five seconds I usually realize I’m holding my breath and force myself to inhale, exhale. I feel huge. Enormous. My legs begin shaking as I imagine myself kicking an entire building to rubble.

After ten seconds I let myself go limp and breathe until the music builds again. Next I tense my stomach, hips, buttocks, and arch my back. Usually I have to tense my arms here, make fists with my hands, because I can’t visualize destroying a building or taking a baseball bat to a computer with my stomach.

I relax again, and then the final round I tense my shoulders, neck, and face. Usually I close my eyes and scream silently. This sounds pretty wild, but honestly it feels great. By this third round, my whole body often shakes with me. Thanks to Nagoski, I know that this is my body using up the stale adrenaline from my constant fear responses.

Earlier this week, I did these muscle-tension exercises three times in a single day. The third round in the afternoon, I wasn’t even bothering to isolate muscle groups. I just tensed every damn muscle in my body, shaking and panting, my hands tearing the covers off my bed and my back arching like I was possessed.

If all of that sounds like something you’d rather avoid, consider that afterwards I feel a deep peace and relief. Moving through the emotion and releasing it is the most profoundly helpful skill I have ever found for dealing with stress.

Are you ever small instead? What if you still feel upset at the end?

Anger doesn’t always make me feel huge. A lot of times it triggers a sense of smallness and helplessness instead. The three-exercise day earlier this week? Most of the day I had felt huge, but I remember that last time I’d felt maybe four inches tall instead. What now?

I visualized myself punching and fighting against the hand of a Giant, someone willing to be rock steady for me and weather my fury. At the end when I lay there in bed, I pulled my weighted blanket over me and visualized myself on the Giant’s chest, their hand heavy and calming over my body. Small and safe.

(Update: I explored this concept in January 2021 in my 2000-word short story Size Erotica: Do for One. One reader review: “This is a remarkable story about personal release and catharsis through size. I think one of the most beautiful things about this fetish of ours, is that it gives us an avenue to experience being powerful, and powerless.”)

I don’t always feel calm at the end. That’s why I’ll usually follow all the exercises with some straw breathing, which is proven to calm your parasympathetic nervous system (the brakes). The pattern I use is breathing in for a count of five, holding for five, exhale for ten or fifteen, hold for five. When you exhale, use pursed lips like you’re blowing air out through a straw. No actual straw needed, but using one can help you get the hang of it.

Sometimes I’ll do a quick guided meditation from MyLife (formerly known as Stop, Breathe & Think), a free award-winning meditation and mindfulness app. My recent favorites include “I Don’t Know & That’s Okay” or “Finding Center in the Storm” from their COVID collection.

I really like the 2-minute visual meditation “Mini: Safe House” because the video has multiple sizey illustrations like a person crying with a house on their head (what a fucking mood) and a huge person standing on top of a mountain. It takes you into a safe home in the woods and tells you to picture the house however you want, so I usually picture a tiny Borrower-style home where I can feel small and safe and hidden. The animal from the meditation usually pops into my head as a soft, cuddly mouse that tells me it’s all going to be okay.

I know it’s not necessarily all going to be okay. But that’s what my body and brain need to hear to complete the stress cycle.

Sometimes I’ll do this while hugging a pillow or—yes, a stuffed animal. (For the record, 40% of adults still have their childhood stuffed animal, and it’s perfectly okay to hold that when you need comfort. We’re primates, damn it, we evolved to hug. It’s a goddamn global pandemic and half of America is unemployed. You can hug a stuffed animal.) For myself, the stuffed animal I use came to me as an adult during a difficult time in my life. I usually close my eyes and imagine it as a surrogate for the huge number of online friends I have in the size community who I wish I could shrink and hug tightly. When I feel too big to function, holding it and imagining it is a human-sized person helps a lot, too.

Would you believe I can do all of the above in about five minutes? I’ll usually take ten just to calm myself, but I’ve done these during Zoom meeting breaks. And each time, my mind feels clearer, I have the capacity to handle normal emotions again, and best of all, my nausea evaporates. (Obviously, if you have nausea and it persists, talk to your doctor.) It makes me wonder how many times throughout my life my inexplicable nausea might have been from unprocessed adrenaline responses.

Even though I haven’t been able to deal with the stressor—respecting the boundaries of the people I’m in conflict with means giving them the space they asked for, gritting my teeth and being patient—I have been able to deal with the stress. A month ago, that meant exercising and doing stress cycle sprints once or twice a week to work through my moderate-to-intense feelings. This week my emotions have been so intense that I have needed multiple muscle-tension exercises a day just so I can keep food down.

But they’re working. I can function. I’m working with my therapist to make a plan for dealing with the stressor itself, but I don’t know if I’d be able to do even that, if I was still trapped under the weight of all the accumulated stress itself. Makes me feel small just thinking about it.

What’s next? Size-themed guided meditations? Somatic revolution?

For years I have toyed with the idea of recording size-themed guided meditations for people in our community. I did a beta run some years ago among a few close friends and never felt happy enough with the recordings to release them. But seeing the intersections of fantasy, kink, and trauma make it clear to me, at least, that there might not ever be a better time to try than right now.

If or when I do summon the energy to create these meditations, I plan to offer some without a sexual component and some with it. Because some of us have the brakes on right now, and that’s okay. And some of us have the accelerators on right now instead, and that’s okay too.

For myself, I’m currently reading My Grandmother’s Hands by Resmaa Menakem, a book on how to process and release inter-generational racial trauma. Menakem is a therapist well-versed in somatic experiencing. (Somatics are a field within bodywork and movement studies which emphasizes internal physical perception and experience.) He offers compassionate strategies and activities for feeling and releasing racial traumas handed down through generations of white and Black families in America. At the rave reviews of a friend I have also picked up The Politics of Trauma: Somatics, Healing, and Social Justice by Staci Haines.

(Update from summer 2021: Menakem has developed his work into Somatic Abolitionism, an embodied anti-racist practice and process of culture building. It’s a phenomenal way to explore the body’s resilience to trauma and injustice on a communal scale. “Somatic Abolitionism requires action—and repeated individual and communal practice. Through repetition, you collectively build resilience, discernment, and the ability to tolerate discomfort that comes with confronting the brutality of race.” I cannot recommend his work enough.)

I’m also doing more research on somatic experiencing and the work of Peter Levine, the researcher and therapist who said, “Trauma is a fact of life. It does not, however, have to be a life sentence.” Over the last 45 years of studying trauma, he developed Trauma Releasing Exercises that sound similar to the muscle exercises from Burnout. However, it appears that they’re intended to activate the Vagus nerve through certain movements and you’re supposed to do them only with professionals who are trained in Polyvagal Theory. With the recent blessing of widely available telehealth options, I’m planning to budget this month for a session with a local yoga therapist trained in this method. If it sheds new light on this process, I may come back and update this article.

(Update from summer of 2021: I worked for a few months with a local yoga therapist to learn some of the yoga poses known to activate the Vagus nerve, and have incorporated those into my muscle tension exercises. The asana known as Setu Bandha Sarvangasana, or Bridge Pose, has helped me the most in achieving the trembling that signals vagal release.)

I sincerely hope that reading this brought some peace of mind to others in our community who have struggled with comparisons lately—either to others, or to their own pre-quarantine sexuality. More than that, I hope that some of the insight on processing trauma helps us survive during quarantine and justice work. If I helped even one person by writing this, it will have been worth it.

The erotic as power

I first encountered Audre Lorde in college, unsurprisingly in the same class where I first heard the word “pansexual.” I wish that professor had introduced us to Lorde’s classic 1978 essay “The Erotic as Power,” a beautiful examination of the feminine sexual power accessible to all people.

I wanted to conclude this blog piece with some of Lorde’s thoughts, in the hope that the few who read this far will see the connection between accepting your sexuality, releasing old trauma, and embracing your erotic power during a time of great pain, fear, and social upheaval—when we need every person willing to work for justice wholeheartedly, again and again.

For once we begin to feel deeply all the aspects of our lives, we begin to demand from ourselves and from our life-pursuits that they feel in accordance with that joy which we know ourselves to be capable of. Our erotic knowledge empowers us, becomes a lens through which we scrutinize all aspects of our existence, forcing us to evaluate those aspects honestly in terms of their relative meaning within our lives. And this is a grave responsibility, projected from within each of us, not to settle for the convenient, the shoddy, the conventionally expected, nor the merely safe…

We have been raised to fear the yes within ourselves, our deepest cravings. But, once recognized, those which do not enhance our future lose their power and can be altered. The fear of our desires keeps them suspect and indiscriminately powerful, for to suppress any truth is to give it strength beyond endurance.

…For as we begin to recognize our deepest feelings, we begin to give up, of necessity, being satisfied with suffering and self-negation, and with the numbness which so often seems like their only alternative in our society. Our acts against oppression become integral with self, motivated and empowered from within.

The community part of “kink community”

A final note. If the response to my poll about this post is any indicator, people may feel moved to share their past trauma in the comments on this blog post and threads on Twitter. I strongly urge you to offer content notices when you do this, and if at all possible, ask people first if they have the energy to hold space for you. Even the act of listening well is a form of emotional labor. It’s one of the best and hardest things humans can do for each other, but it’s still labor.

Sharing trauma is a profound act of vulnerability, visibility, courage, and solidarity—and it can also re-traumatize people for a variety of reasons, who then may not have the skills, resources, or ability to be present with you the way you deserve. I strongly recommend exploring low-cost telehealth therapy and counseling options in your local area using inclusivetherapists.com and openpathcollective.org, especially those who are sex-positive and kink-knowledgable, who will celebrate your identities.

The world is burning. The day that this post finally goes live, I have learned a close friend of mine is exhausted from illness and awaiting COVID test results. My whole polycule, myself included, is depressed. When I return to work in the nonprofit field tomorrow morning, I will draft press releases to prepare for the inevitable deaths from the pandemic as the state of Texas forces schools back open.

Day to day, I don’t know what energy reserves I will have to devote to honoring what people share with me. I want to hold space for everyone, and wish that I would always be able to show up in every way possible. But the world is burning. It’s okay for us to rest, to need help, and to ask for others to show up, too.

That’s what community is for, after all. Compassion is best when shared.

Be First to Comment